Musica Futurista is a collection of music and spoken word from the Italian Futurist movement 1909-1935, including original recordings made by Filipo Tomasso Marinetti and Luigi Russolo.

As well as vintage free-verse readings by Futurist founding father Marinetti, this popular primer includes recordings of the celebrated intonarumori (noise intoners) devised by Russolo, including a fragment from his lost landmark work The Awakening of a City.

Alongside restored archive recordings, the 73 minute album includes performances of key Futurist musical works by Balilla Pratella, Luigi Grandi, Silvio Mix, Aldo Giuntini, Franco Casavola and Alfredo Casella by leading contemporary interpreter Daniele Lombardi.

The CD booklet features archive images and detailed historical notes.

Tracklist:

1. F.T. MARINETTI Definizione di Futurismo

2. FRANCESCO BALILLA PRATELLA War (La Guerra)

3. F.T. MARINETTI La Battaglia di Adrianopoli

4. LUIGI RUSSOLO The Awakening of a City

5. ANTONIO RUSSOLO Corale + Serenata

6. F.T. MARINETTI Sintesi Musicali Futuriste

7. ALDO GIUNTINI The India Rubber Man

8. LUIGI GRANDI Dogfight (Aeroduello)

9. SILVIO MIX Two Preludes

10. FRANCO CASAVOLA Prigionieri + Dance of the Monkeys

11. ALFREDO CASELLA Pupazzetti

12. F.T. MARINETTI Parole In Liberta

13. MALNECK & SIGNORELLI Futurist Caprice

14. F.T. MARINETTI Five Radio Syntheses\

Reviews:

"Of the major early 20th century artistic movements, Futurism is widely acknowledged as a major influence, and the first in which music and performance were major elements. Musica Futurista contains the first substantial recordings of Futurist music, digitally remastered and with two additional tracks. The booklet text by James Nice is informative" (The Wire, 09/2004)

"The influence of these works can be seen across multiple genres, from modern composition to avant rock and electronica" (Brainwashed, 08/2004)

"A terrific collection" (All Music Guide)

"A beautiful and serene re-examination of explosive thinkers and the bombs they loved. One of the most important records released this year" (Paris Transatlantic, 06/2006)

Musica Futurista: The Art of Noises

In his founding Manifesto of February 1909, Futurist leader Filipo Tomasso Marinetti confirmed that the Futurist ideology would include sound and noise in the armoury of the war against traditionalism. The roar of a motor car, so he claimed, was more beautiful than anything by Michaelangelo. Moreover Futurists would 'sing in praise of the gliding flight of aeroplanes with their propellers screeching in the wind like a flag, and their roar reminiscent of the applause of an enthusiastic crowd.'

However, Marinetti concerned himself chiefly with poetry and literature, and the first Manifesto of Futurist Composers would not appear for another two years. Published in January 1911 by Francesco Balilla Pratella (1880-1955), though tweaked by Marinetti, the text was hurled like a grenade into the midst of the prevailing culture. Condemning existing musical forms such as opera and bel canto as anti-progressive, Pratella exhorted 'young composers' to abandon the old order and adopt 'free study' as a means of regeneration. The future, he wrote, lay in: 'The liberation of individual musical sensibility from all imitation or influence of the past. To feel and sing with the mind turned to the future, drawing inspiration and aesthetics from nature, through all the human and non-human phenomena present in it. To exhalt man as a symbol that is constantly renewed by the varied aspects of modern life and in its infinity of intimate relationships with nature.'

For all his rhetoric, Pratella was an essentially conventional composer, and the 1911 Manifesto was remarkably vague in discussing contemporary musical trends. The only German mentioned was Richard Strauss, praised for his 'struggle to fight the past with innovation and ingenuity' despite being handicapped by commercial instincts and a 'banality of soul'. In France, Debussy was singled out as defying tradition, along with the 'musically inferior' Gustave Charpentier. Other Europeans deemed worthy of note included Elgar, Mussorgsky and Sibelius, but none of them were radicals, and all had been born well before 1870.

In fact the Manifesto was outdated even before it appeared. Pratella had drawn from earlier essays by Ferruchio Busoni and Domenico Alaleone, and his text was somewhat provincial. Between Paris, Vienna and Berlin radical new music was being produced by composers such as Ravel, Satie, Bartok, Stravinsky (lately arrived in France with Diaghilev) and the Schoenberg school. For all his talk of liberation and Futurism, Pratella had identified Debussy alone.

Two months later, in March 1911, Pratella published his Technical Manifesto of Futurist Music, followed in July 1912 by The Destruction of Quadrature. Both promoted free or irregular rhythms, enharmonic music, atonality, polyphony and micro-tones. Pratella later collected all three Manifestos in a single volume, which also contained a piano score for his own composition, Futurist Music for Orchestra. Although it bears little trace of atonality, the piece still managed to cause a stir when first performed at the Teatro Costanzi in Rome in 21 February 1913. There, amidst uproar from the audience, the bewildered composer rushed from the stage in panic, complaining to Marinetti that half the orchestra had disappeared. Pratella followed Futurist Music with an opera, L'Aviatore Dro, written in 1915 and first performed in 1920. Despite some provocative captioning, however, and the use of intonarumori (see below) as the hero's plane crashed into the ground, the piece was essentially conventional.

If Pratella failed to put his theories into practise in his own music, his proposals would have a profound effect within the Futurist movement. The principle exponent was the painter Luigi Russolo (1885-1947), whose vast canvas Music from 1911-12 had already depicted its subject as a swirl of keyboard crescendos assailing the player's head. In March 1913 Russolo published The Art of Noises (L'arte dei rumori), now seen as the true manifesto of Futurist music, and far closer to Marinetti's radical conception of free words (parole in liberta) than Pratella's fuzzy theorising.

In The Art of Noises Russolo flaunted his anti-qualifications with pride: 'I am not a musician by profession, and therefore I have no acoustical prejudices, nor any works to defend. I am a Futurist painter who projects beyond himself, into an art much-loved and studied, his desire to renew everything. Thus, bolder than a professional musician, unconcerned by my apparent incompetence, and convinced that my audacity opens up all rights and all possibilities, I am able to divine the great renewal of music by means of the Art of Noises.'

Using Pratella's theories as his starting point, Russolo declared that 'noise is triumphant and reigns sovereign over the sensibility of men. 'Instead of conventional melodies and sounds, predictably ordered, he proposed a form of musique concrete including noise, din and cacophony, be it the primary sounds of nature or the roar of machines in the modern city. 'Let us cross a great modern capital with our ears more alert than our eyes. We will delight in distinguishing the eddying of water, of air and gas in metal pipes, the muttering of motors that breathe and pulse with an indisputable animality, the throbbing of valves, the bustle of pistons, the shrieks of mechanical saws, the jolting of trams on the tracks, the cracking of whips, the flapping of awnings and flags. We will amuse ourselves by orchestrating together in our imagination the din of rolling shop shutters, slamming doors, the varied hubbub of train stations, iron works, thread mills, printing presses, electrical plants and subways.'

To this end Luigi Russolo began to construct noise intoners (intonarumori) in his Milan laboratory, where he was assisted by another likeminded painter, Ugo Piatti. The intoners were essentially crude synthesisers, intended to reproduce a variety of modern noises, and able to regulate their harmony, pitch and rhythm. The instruments contained various motors and mechanisms operated by means of a protruding handle, while pitch was varied by means of a lever and a sliding scale.

The Art of Noises was quoted and discussed in a variety of journals and newspapers across Europe, and mocked more often than not. The first intonarumori demonstration came on 2 June 1913 at the Teatro Storchi in Modena, when Russolo unveiled an exploder (scoppiatore) which reproduced the sound of an internal combustion engine with a range of ten notes. Most of those in the 2000 strong audience were not yet ready to adopt his 'Futurist Ear', however, and a flurry of enraged newspaper articles accused Russolo of producing a cacophonous din devoid of logic, based on an elitist theory intended to shock the bourgeois. In fact din seems an unlikely descriptive term, since Russolo was too early to profit from electrical amplification, and instead relied on large megaphones to project his noises - an unsatisfactory arrangement which may in part explain why most of his early public performances may be objectively judged as failures.

Russolo answered his critics in a series of articles in the magazine Lacerba, and at the same time explained the mechanics of the intonarumori: 'It was necessary for practical reasons that the noise intoner be as simple as possible, and this we succeeded in doing. It is enough to say that s ingle stretched diaphragm placed in the right position gives, when its tension is varied, a scale of more than ten tones, complete with all the passages of semi-tones, quarter-tones and even all the tiniest fractions of tones. The preparation of the material for these diaphragms is carried out with special chemical baths, and varies according to the timbre of noise required. By varying the way in which the diaphragm itself is moved, further types and timbres of noise can be obtained while retaining the possibility of varying the tone.'

By the Spring of 1914 Russolo and Piatti had constructed four intonarumori - the exploder, crackler (crepitatori), buzzer (ronzatori) and scraper (stropicciatori) - and had published scores for two 'noise networks' titled Risveglio di una città (The Awakening of a City) and Convegno d'aeroplani e d'automobili (The Meeting of Automobiles and Aeroplanes). Thus prepared, Russolo gave a salon demonstration of this new music at the house of Marinetti, attended by sundry Futurists (Pratella included) as well as Igor Stravinsky, Sergei Diaghilev and Leonide Massine. Indeed Stravinsky had already expressed interest in incorporating a noise intoner in one of his ballets. In his memoir Le serate futuriste (1930), Francesco Canguillo recalled the evening thus:

'Pratella, the swan of Romagna, arrived in Milan hoping to find that none of the guests had turned up, and that he would not have to play a note. But he was dragged to the piano and forced to play and sing his music with a mouth that would rather have opened to a good bowl of fish soup. Somehow or other the piece was finished, and Russolo approached one of the eight or nine Noise Intoners. A Crackler crackled and set up a thousand sparks like a gloomy torrent. Stravinsky leapt from the divan like an exploding bedspring, with a whistle of overjoyed excitement. At the same time a Rustler rustled like silk skirts, or like new leaves in April. The frenetic composer hurled himself on the piano in an attempt to find that prodigious onomatopoetic sound, but in vain did his avid fingers explore all the semi-tones.

'Meanwhile the male dancer [Massine] swung his professional legs. Diaghilev went 'Ah, Ah' like a startled quail, and that for him was the highest sign of approval. By moving his legs the dancer was trying to say that the strange symphony was danceable, while Marinetti, happier than ever, ordered tea, cakes and liqueurs. Boccioni whispered to Carra that the guests were won over. The only person who remained unmoved was Russolo himself. He tweaked his goatee beard and said that there was a lot to modify: he hated praise. As a polite murmur of disagreement started, Piatti declared that experiments would have to begin again from scratch. Stravinsky and the Slav pianist played a frenzied four-handed version of the Firebird, and Pratella slept soundly through it all.'

The first public performance with the intonarumori took place at the Teatro dal Verme in Milan on 21 April 1914. Russolo and Piatti were due to perform three pieces (The Awakening of a City, The Meeting of Automobiles and Aeroplanes and Dining on the Hotel Terrace), but following a rehearsal during the afternoon the show was banned by the police on the grounds that it was likely trigger a public disturbance. After two local politicians intervened on the side of the Futurists the show went ahead, with predictable results. Russolo recalled that 'the immense crowd were already in uproar half an hour before the performance', with missiles were thrown throughout, abuse supposedly led by 'past-ist' music professors from the Royal Conservatory of Milan. The noise of the brawl drowned out the new music, and Marinetti later described the experience of demonstrating the intoners to an incredulous public as 'like showing the first steam engine to a heard of cows.'

Russolo was afterwards obliged to appear in court, having struck Agostino Cameroni, a critic from the Catholic newspaper L'Italia, who was said to have published 'insults and frivolous defamations' of Futurism. Russolo was acquitted and gave a second performance in Genoa on 20 May, although the show was judged a failure after his original intonarumori performers were unable to attend, and replaced with untrained substitutes at the last minute.

Russolo and Piatti were still less successful in London in June. At the Coliseum the pair gave twelve performances of The Awakening of a City and The Meeting of Automobiles and Aeroplanes, billed as two 'noise spirals' generated by an 'orchestra' of 23 intonarumori, including buzzers, scrapers, exploders, cracklers, gurglers (gorgogliatori), roarers (rombatori), howlers (ululatori), rustlers (frusciatori), whistlers (sibilatori) and croakers (gracidatori). Marinetti also delivered a lecture on the new Art of Noises, but the first of these shows generated only puzzlement and hostility. It hardly helped that Russolo was obliged to man his intonarumori with bemused musicians from the Coloseum house orchestra. According to the English Futurist Richard Nevinson, writing in his memoir Paint and Prejudice (1937):

'Marinetti swaggered onto the vast stage looking about the size of a housefly and bowed. As he spoke no English there was no time wasted with explanations or in the preparation of his audience. Had they understood Italian, I do believe Marinetti could have magnetised them as he did everybody else. There was nothing for it, however, but to call upon his ten noise-tuners to play, so they turned handles like those of a hurdy-gurdy. It must have sounded magnificent to him for he beamed, but a little way back in the audience, all one could hear was the faintest of buzzes. At first the audience did not understand that this was the performance offered them in return for their hard-earned cash, but when they did there was one vast, deep and long sustained 'Boo!''

Nevinson's account suggests that fewer intonarumori reached London than anticipated, while the addition of an Elgar gramophone record to play over the top of Futurist pieces on subsequent nights prompted only stony silence. If music is language, it seems that London audiences found Russolo even less comprehensible than Marinetti. By the end of the run, several thousands of people had been exposed to the music of the Future. Yet although Marinetti deemed the season a triumph, the British press were less effusive. According to the Times on 16 June, the music from Russolo's:

'Weird funnel-shaped instruments resembled the sounds heard in the rigging of a channel-steamer during a bad crossing, and it was, perhaps, unwise of the players - or should we call them 'noisicians? - to proceed with their second piece. After the pathetic cries of 'no more' which greeted them from all the excited quarters of the auditorium The audience seemed to be of the opinion that Futurist music had better be kept for the Future. At all events, they show an earnest desire not to have it at present.'

The outbreak of the First World War curtailed Futurist activity outside Italy, and killed Russolo's plans for further European performances. Marinetti and other Futurists enlisted in the Lombard Volunteer Cyclist Battalion in July 1914, apparently the speediest unit in King Victor Emmanuel's army, although Italy did not enter the war until May of the following year. But Italy's war was conducted in a haphazard and incompetent fashion, and would cost the Futurists dear. According to Marinetti, thirteen of their number were killed, and forty-one wounded. Luigi Russolo, the creator of noise spirals and the intonarumori, suffered a serious head wound at Monte Grappa in 1917 which required cranial surgery and a year of recuperation. It seems likely that this injury caused him to reconsider his earlier appraisal of modern war as a 'marvellous and grand and tragic symphony.'

In June 1921 Russolo and his younger brother Antonio (1977-1942) staged a performance at the Théâtre des Champs Elysées in Paris, from which a quarrelsome Dada faction lead by Tristan Tzara had to be forcibly ejected. Here Russolo demonstrated how the intonarumori might work as part of a conventional orchestra, and possibly performed the Corale and Serenata recorded by Antonio in 1924. But Dadas such as Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes gave the Futurists short thrift. "The Italian bruitistes, led by Marinetti, were giving a performance of works written for their new instruments. These works were pale, insipid and melodious in spite of Russolo's noise-music, and the Dadaists who attended did not fail to express their feelings - and very loudly. Marinetti asked indulgence for Russolo, who had been wounded in the war and had undergone a serious operation on his skull. This moved the Dadaists to demonstrate violently how little impressed they were by a reference to the war."

Later innovations included a noise harmonium (rumorarmonio) and an enharmonic bow, and Russolo provided live soundtracks to several avant-garde films at Studio 28. However the advent of talking pictures closed this avenue, and Russolo performed in public for the last time in 1929. Tasting poverty and disappointment, he abandoned Futurism in favour of mysticism, supernature and the occult, publishing his book Beyond the Material World in 1938 and passing away on 4 February 1947.

Luigi Russolo is without doubt one of the most underrated figures of the 20th century avant-garde. It is tragic that none of his instruments survive today, and that most of his music scores are also lost. As John Cage observed ruefully in 1946, as a composer Russolo exists only as a name, it being his fate to be a pioneer decades ahead of his time, and the requisite technology. Although his extraordinary ideas met with fierce resistance, his work exerted a powerful influence on a number of leading avant-garde and experimental composers, initially Igor Stravinsky, George Antheil and Arthur Honegger, and later John Cage, Edgard Varese, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Harry Partch, as well as 'non-classical' electronica and avant-rock. Force of circumstance means that this CD can only offer a small part of the canon of Futurist music, but these tantalizing fragments are no less fascinating for that.

James Nice

$13.99 - Sold Out

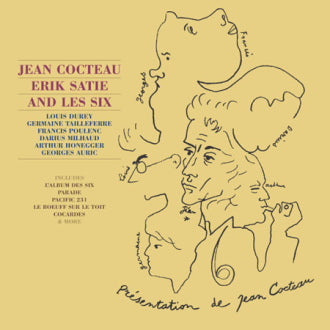

The celebrated L'Album des Six of 1920 represents a small landmark in the development of 20th century modernist music, featuring music by Francis Poulenc, Arthur Honegger, Georges...